What is an Apparatus

I was Chinese artist for a day is the first work in this ongoing project investigating the relationship between various perspectives of history, power and identity. There are many topics in question here: the matter of the institution of the museum and its role in shaping historical validity, human conception of the future, the insatiability of the markets, valuation of art, power of the state and last but not least the role of the artist.

Through the first gesture of this narrative, the artist acquires a fictional and questionable identity. It allows him, metaphorically, to traverse borders and limits in a way which is only available through the artistic act.

The large format self-portrait presents the artist proudly stating his affiliation even if for a day (I was Chinese artist for a day). He appears here perhaps like a sort of activist, even though the details make him look more an exemplary user of a social media platform (the green is unrealistic and as such becomes an exemplary colour constructing visual identity, alike to the Facebook’s use of blue). This brings in question the subjects of the contemporary human evaluation, creation of virtual identities, social control, and thus the matter of individual freedom.

This work further investigates the artist’s status through his mode of affiliation and on the other hand through the dramatic pursuit of freedom, which is the condition of the romantic model of the artistic existence (in turn only possible through the act of abolishing any forms of affiliation). Here, the national identity becomes invalid in a twofold way: through it being aestheticized (turned into a work of art) and through the validity date on the fabricated document (i.e. the id card had expired before it reached the artist). In this sense, this work hints towards the subject of national identity from the perspective of it being already history.

2016

On 18th October 1965, a talk between Marcel Duchamp and Martin Friedman took place – both gentlemen present in dinner suits, seated in the foyer of Walker Art Center in front of a large Frank Stella painting, with the former smoking a cigar.

It is curious to see how Duchamp, always conscious of symbols and attributes at the beginning of his life remained faithful to the pipe (associated with solitary and intellectual individuals) to, later on, switch to cigars (associated with power and wealth) which he also smoked incessantly. He then made sure to be often portrayed smoking one, as he did with pipe beforehand, even on a public occasion and furthermore in a place like a museum.

Of course, from the contemporary perspective an image of anybody smoking in such a place is at the very least surprising, but would it actually be otherwise back in 1965?

Despite statesmen often being seen in historical photographs holding on to their cigars during parliamentary sessions or at the general assembly, the US Congress banned smoking within its chambers as early as 1914, whereas the UK parliament banned smoking in the lower chamber in 1964. Smoking in churches and at holy sites was banned way earlier. Specifically, in 1624 Urban VIII issued a ‘worldwide ban on smoking in holy places’ threatening the offenders with ex-communication. And it was precisely the churches that could be considered the earliest public institutions where one could see art. I believe this smoking taboo to permeate into the later museum from thereon.

Yet, despite all that, it appeared as if normal for Duchamp to keep his attribute in such place and such context. And when confronted with such an image the issues of power and status within the structures of an institution resurface immediately. In a sense, it should not be the least surprising. The Gin Act of 1751 limited the consumption of gin, not whisky (which was consumed by the rich) and perhaps smoking cannabis in the US became criminalised because it was oftentimes smoked by the southern migrants, on the contrary to tobacco.

Duchamp seems to have switched to this new attribute of power precisely towards the end of his life when he acquired an ‘institution’-wide recognition and status. The installation is re-enacting this historical event within the institutional space, enclosing the smoke, for the spectator to be only permitted to observe from the ‘outside’.

After all, the structures of power within the institution devoted to the ‘free activity’ (which I understood art to be) are as limiting and hermetic as they can be. Only those accepted can share the Sacred Pipe and become part of the historical ‘truth’.

2017

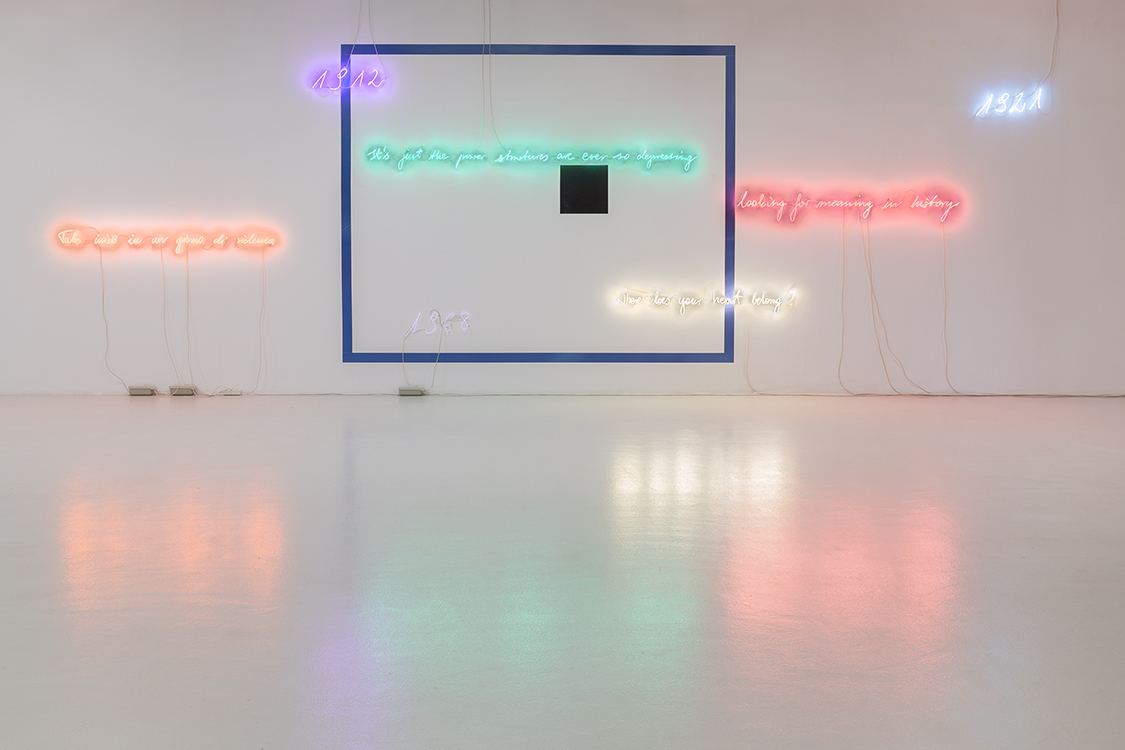

The artist signed ‘It’s just the power structures are ever so depressing’ within a ‘framing’ arrangement made out of a photographic wallpaper. What appears to be an abstract composition is in fact fragment of a photograph taken from another work: Source Book: Art in XXI century – a book containing 81 images of the rabbit Josephine. Thus, the complexity of this simple statement comes from the reading of its framing: at first, it seems a modernist abstract composition, then the Black Square as a symbolic element within the historical discourse of the artist and then individually constructed symbolic language within an artistic practice. Furthermore, it seems plausible to assume the feeling of ‘depression’ comes precisely from the order in which the deciphering occurs.

The work produced by an artist is by default framed by art history and thus historic references or associations are unavoidable. The metaphorical frame could be understood to represent a constraint of history, or an institution which is, among others, historically implicated (and these historical implications and history are predetermined largely by power structures). However, a form of freedom is already achieved in the acceptance of necessity of the frame, here, specifically in the form of the rabbit Josephine. The depression is not so much self-directed at the artist thus but rather moved onto the spectator who becomes, in most cases, incapable of establishing associations outside of the frameworks or language already established.

The title 喜坑 (Auspicious hole) refers to a specific term used in Qing Dynasty China. The auspicious hole/pit used to describe a hole in the ground, whose location was designated by an astrologist to bury the placenta of a new born in. The location was decided individually and was meant to influence the rest of the child’s life, thus great care would be taken to determine the desired ‘auspicious’ place.

Here, in a somehow absurd way the hole is represented by the supposed Black Square. It thus becomes apparent in the context of the modern tradition, history or identity the image is destined to be read precisely in the predetermined way influenced by the power of tradition and establishment.

2019

I was Chinese artist for a day

(2016) chromogenic print 100x80 cm

I was Chinese artist for a day

(2016) ID card 5,4x8,6 cm

喜坑 (Auspicious hole)

(2019) photographic wallpaper, neon, 360x280 cm

Marcel Duchamp smoking cigar in the museum

(2017) neon, smoke, dimensions variable