Sous les Pavés, la Plage !

Sous les Pavés, la Plage! (Under the cobblestones, the beach!) was one of the slogans used in France’s 1968 protests. It expressed the desire that beneath the city, hardened by stone, lay the freedom of the beach (represented by the sand on which the paving stones were placed). Martychowiec’s installation subverts this slogan, replacing the sand, a symbol of nature and freedom, with industrially produced glass crystals. This seemingly simple substitution serves as a poignant critique of contemporary notions of freedom, suggesting a shift from the authentic desire for liberation in 1968 to a consumerist-driven ‘freedom’ often associated with material acquisition and curated experiences.

The installation’s visual language is deceptively inviting. Blue walls, beach chairs, and umbrellas evoke nostalgic images of carefree holidays, yet the substitution of sand with cold, lifeless crystals creates a sense of unease. This unsettling juxtaposition mirrors the artist’s broader critique of the post-1968 neoliberal landscape, where the pursuit of individual liberty has been supplanted by passive consumption. As the artist notes, ‘Violence and freedom are the two ever-present aspects of human civilisations,’ and in this work, the utopian ideals of the 1968 protests are contrasted with the stark realities of a society increasingly pacified through materialistic fulfilment.

The crystals, a recurring motif in Martychowiec’s oeuvre, symbolise this shift towards artificiality and commodification. In Sous les Pavés, la Plage!, they transform the beach, a symbol of unbridled nature and escape, into a sterile, manufactured environment. This transformation mirrors the broader societal shift where authentic experiences are replaced by carefully curated simulacra, and the pursuit of freedom is reduced to the acquisition of material goods.

The installation’s aesthetic appeal draws the viewer in, only to confront them with an underlying message of disillusionment and unease. The crystals, while visually stunning, are ultimately cold and sterile, a stark reminder of the emptiness that can accompany a life defined by material possessions. Through this powerful juxtaposition, Martychowiec encourages viewers to question the authenticity of their own desires and to seek a deeper understanding of freedom beyond the confines of consumerist culture.

Another version of the installation expands upon its original form, transforming into an active, participatory space. This ‘beach’ invites visitors to shed their inhibitions and engage in a variety of activities: sunbathing, playing, taking photos, or simply relaxing in beach chairs. By evoking a primal setting, the beach prompts reflection on contemporary existence through the lens of our shared human nature.

Furthermore, this participatory version critiques the role of the museum in consumer-driven societies. It challenges the museum’s evolution from an institution validating art history to one focused on attracting audiences and offering lifestyle fulfillment. By encouraging free, self-organized collective activity, the installation questions the museum’s institutionalized nature, the freedom of artistic creation, and the politicized implications of historiography.

The installation seamlessly integrates into the museum’s architecture (as visualized in a proposal for CAFA Museum in Beijing). The slogan ‘Sous les pavés, la plage!’, a famous act of ‘vandalism’ from the 1968 protests in France, is sprayed on a grey wall. However, unlike the original street graffiti, this text appears within the museum, a public space with a different function. The museum is traditionally used for storing, studying, and protecting cultural artifacts, but it also excludes certain forms of expression.

The slogan’s placement high on the wall creates a dual effect. On one hand, it suggests the institution has been reclaimed by the masses, who assert their collective political voice in place of the individual artist. On the other hand, the reference to 1968 serves as a reminder that the masses, without organization and relying solely on slogans, can become susceptible to pacification. This is evident in the scene below, where a society fulfills its role through the consumption of lifestyle products, fashion, and even art.

2014

Supreme artist’s breath

The artist places his physical product in a container representing structures of the contemporary society (the Supreme ball). In the process, the act is placed and follows a historical narrative (Duchamp -> Manzoni -> Martychowiec).

This paraphrasing gesture is reversing the original one (Warhol); it brings the creative act back from the work of consumption to the work of (basic) physical creation, and most importantly, towards the narrative it is attempting to redirect.

The film’s value emerges, as with most of the artist’s works, in a relationship to the other products of his practice. In this sense, the film’s function is that of a documentation. What matters is what becomes of the branded artist’s breath. In one case it becomes a hidden symbolic and metaphorical object within a conceptual work of art by the same artist (Sous les pavés, la plage !). At the same time, another one becomes encapsulated within a glass cube. The product of the artistic activity (creation) and the product of the contemporary consumerist society (consumption) belong both to the same time, and as such are contained and preserved within a sort of airtight archaeological display together, as if they were both objects of times long gone, and both became part of history.

The video documentation constitutes to the myth of the artist who inhales history and exhales his own creation. This, in its own right, is sufficient and thus he boldly pronounces his name towards the end of the activity, as if he was signing his work.

As Hölderlin writes “What remains the poets provide”. The remnant in question is a relic of the mythical act which as the historical necessity dictates, proliferates here and there.

2017

What remains the poets provide

reenacts a historic work by Giovanni Anselmo – Hand indicating. It marks another point in Martychowiec’s historical narrative and, specifically, positions his practice in context to the passed post-modernity. Anselmo’s strong gesture, as its title suggests, offers essentially an empty hand and thus not what normally the hand would hold, but rather the direction. Hence, what is developed within the discourse is the framework rather than the value of individual elements – a typical post-modern approach. What Martychowiec is, however, indicating, is importance of symbolic elements, whose value and meaning are developed within his continuous artistic practice. The direction is suggested, but its value and meaning can only be determined in regards to the specific signifier. This symbol, among others, can be found in his preceding but also future works and the means to read it are offered throughout his body of work. In case of this narrative the crystal, the Supreme, they both represent specific historical and political conditions which become some of the topics of Martychowiec’s story.

The title of the work is taken from poem Andenken, in which Friedrich Hölderlin declares what poetry is: poetry is founding by the word and in the word, and what is established in this way is – what remains. The poet names the gods and all things with respect to what they are and thus they come into being. In this way, the artistic symbols, once develop, acquire ‘life of their own’ and can function independently outside of their initial paradigm, of course, with the possibility of being always traced back to it and read within it.

2018

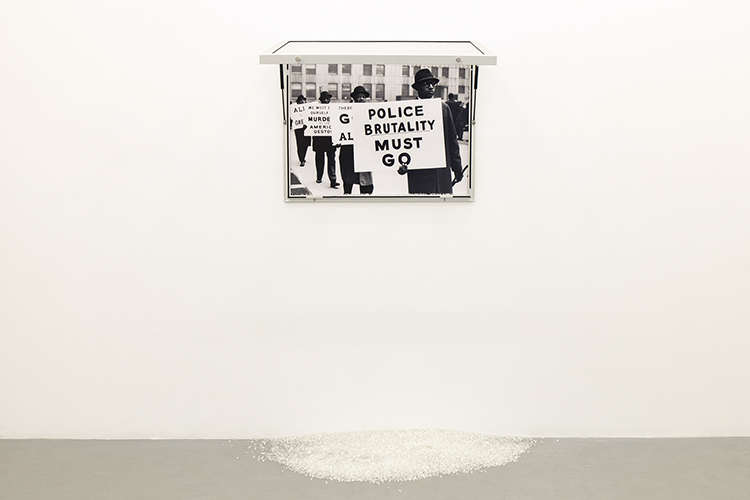

[…] we face an image whose part is covered with a layer of crystals Sous les pavés, la plage! (1989). The date included in the title is one suggestion but for those familiar with the events in Beijing at that time the image is known. It is the nicknamed ‘tank man’ – an unidentified Chinese man who stood in front of a column of tanks leaving Tiananmen Square on June 5, 1989, the day after the Chinese military had suppressed the Tiananmen Square protests.

The displays have a twofold mean of presentation. The display closed with a layer of crystals covering part of the historic image, or open, with crystals pouring out on the ground and the full image revealed. However, only one in custody of the display has the power to open it. And it is common for those in power to prefer certain parts of history to be forgotten. The artist is utilising historical images as representations of an ongoing struggle between freedom of the individual will and the power system. In such way the event depicted becomes symbolic representation of something repeated in history.

2018

Several of the sculptures titled Arte povera are made using concrete pavement plates and glass crystals. At first, it would seem the title could be taken quite literally as the ‘poorness’ of this art reflects the generic value of materials it has been made with (glass and concrete). The crystal arrangements attract the spectator with their sparkles which contrast with the rough concrete grey surface. They appear attractive, although one might ask, why would such ‘poor’ and common materials attract?

The original arte povera’s political dimension had to do with general modes of art’s valuation at the time. These works, on the other hand, offer a certain personal mirroring and questioning of our contemporary condition. Some of the sculpture refer to other historical works from the arte povera movement. E.g. one of the later works (2022) seem to resemble a tombstone of a sort. However no inscription has been made in the ‘stone’ – no name, no date or in memoriam. The spectator might fail to find answer as to why the work attracts. Is it art that is ‘poor’? Or is it that our life deprived of history has become so?

2020

Hamburger, one could argue, is one of the symbols of consumerism and it was for that reason Danish filmmaker Jørgen Leth asked Andy Warhol to make an appearance eating one in his film 66 scenes from America from 1982.

Since times of Warhol mass consumerism did not spare any field, including that of contemporary art, making it often a product of not so much a unique and rare experience but rather a ‘daily bread’.

The act of Warhol was quasi-reenacted by Martychowiec in his video from 2017 Supreme Artist’s Breath. The work is esoteric due to the historical narrative it is constructed upon but it clearly suggests the questions of importance of reading of a work of art and historical consciousness within the context of consumerist societies.

Go eat your burger! is a work which follows this line of thought. A sarcastic statement, one could think, compares and equalizes the act consumption of art with that of fast food (fast art?). It directs the viewer of art (which was classically understood a part of ‘high culture’) towards a ‘lower’ and more mundane activity.

But can such interpretation be assumed when one was to consider the act of Warhol or the later film by Martychowiec? It could be said this work is framed by history, and offers completely different meaning to those who are able to see such intricate historical frame. So. in fact this work calls upon awakening of a sort of historical consciousness. Once in effect, even a gesture of activity as mundane as eating a hamburger can acquire deep meaning.

2020

The supreme sequence is a work combining various symbolic elements from throughout Martychowiec’s practice.

In 1202 Leonardo of Pisa, known as Fibonacci introduced a sequence of numbers which later mathematicians, like Kepler, researched from the perspective of, among others, their reference to nature, for example by using it to explain pentagonal shape of flowers, forms of plants, trees, functioning of bee populations, etc. In fact, the sequence, and its relation to the golden ratio inspired both artists and scientists, from Renaissance painters to Le Corbusier, who made it central point of reference in his search for perfect proportions.

Interestingly, the sequence found its source in Fibonacci’s study of the growth of the rabbit population. Rabbit Josephine plays one of the central roles in Martychowiec’s work, placed on the opposing side to the panda.

The other important reference is the Black Square, which just like the pursuit of historical mathematicians was an attempt of representing all through one idea.

How does then contemporary man fit in all of this? A square piece of fabric was given to a tailor. The striped pattern and colours have previously been used in the installation Sous les pavés la plage and another red square reading ‘Supreme day cream’ was installed within a historical Go game in the Reading history project. ‘Black square turned red square turned a product of daily [=non-historical] consumption’ wrote the artist at the time. Out of this fabric, a shape was cut out to allow making of a pair of shorts for a porcelain panda (Sur la plage). Panda itself in the artist’s work represents a new human scale and its height – ‘the historic level’. Like the golden ratio’s spiral placed across squares representing the seqence, the remaining of the square fabric creates an imaginary sequence representing what remains of life in the age of consumption.

2021

Martychowiec started working on the series of works under the title ‘Arte povera’ early on in 2020. […] The new sculptures which the artist began making towards the end of 2021 were created with crystals and museum/art fair/gallery promotional merchandise.

The arrangements of canvas bags remind of another Arte povera artist – Jannis Kounelis’s bags filled with coal. And although the reading of these works from the perspective of art history might immediately come to mind it would be fair to say other equally important perspectives of the works lie in their critique of the institution and commercial societies.

How to take then exactly these simple readymades? In the beginning one could look at tote bags as a reference to the institutionalized art and its place in mass culture: how art is marketed and how we consume it? And then, what it gives us in return?

The bags art lovers carry around on daily basis advertising particular institution-brands are filled to the brim with glass crystals. They are perhaps too heavy to carry around. One could then ask: what exactly is the weight and value of what we ‘carry out’ from the contact with art.

Naturally, both bags and crystals are not of high material value, as much as the materials originally used by Arte povera artists in the 60s. Their exclusivity is only in ‘appearances’ and thus their symbolic value is, likewise, only apparent. For instance, branded tote bags are either granted to VIP visitors of the art fairs or they advertise exclusive institutions and thus these ‘poor’ objects carry certain exclusivity. And for this reasons these works always hold some kind of reference to the historical format of the structures of power.

The sparkle might be as attractive as it is ‘dead’ (Beuys) and artificial (deprived of natural connotations and sensorial delights work of Kounelis might be offering). Like with the pavement blocks encrusted with crystals the spectator is forced to ponder: is it poor art, or is it our life that has become so.

Sous les pavés, la plage !

(2014) sculpture: glass crystals, inflated beach ball, beach chair, umbrella, oil pastel, humidifiers, halogen lamps

Sous les pavés, la plage !

(2014) interactive installation: glass crystals, plastic inflated balls, beach umbrellas, chairs and other accessories, halogen lamps, air humidifiers, bar and changing rooms furniture, beverages

Supreme artist's breath

(2017) HD Video 00:02:51

Supreme artist's breath

(2017) object: inflated ball, airtight glass cube

What remains the poets provide

(2018) chromogenic print 130x100 cm

Arte povera

(2020) concrete pavement plates, glass crystals

Arte povera

(2020) concrete pavement plates, glass crystals, 40x40 cm

Sous les pavés, la plage! (1967)

(2018) Alluminium display 76x92 cm, photographic print on aluminium, 33 000 glass crystals

Sous les pavés, la plage! (1989)

(2018) Alluminium display 76x92 cm, photographic print on aluminium, 20 000 glass crystals

Go eat your burger!

(2020) neon 25x117 cm

Supreme sequence

(2021) polyster, 150x150 cm

Sous les pavés, la plage! (1868)

(2018) Alluminium display 100x68 cm, photographic print on aluminium, 17 000 glass crystals

Sous les pavés, la plage! (1981)

(2019) Alluminium display 76x92 cm, photographic print on aluminium, 48 000 glass crystals

Sous les pavés, la plage! (1963)

(2019) Alluminium display 76x92 cm, photographic print on aluminium, 44 000 glass crystals

Sous les pavés, la plage! (1942)

(2021) Alluminium display 76x92 cm, photographic print on aluminium, 35 000 glass crystals

Sous les pavés, la plage! (2017)

(2021) Alluminium display 76x92 cm, photographic print on aluminium, 40 000 glass crystals

Arte povera (magnet)

(2021) museum merchandise, glass crystals

Arte povera (special relationship)

(2021) museum merchandise, glass crystals

Arte povera (coachman)

(2022) museum merchandise, glass crystals

Arte povera

(2022) concrete pavement plate, glass crystals, dimensions variable

Arte povera (triumvirate)

(2022) museum merchandise, glass crystals

Arte povera (baucans)

(2022) museum merchandise, glass crystals

Arte povera (blue blood)

(2022) museum merchandise, glass crystals

Sous les pavés, la plage! (1921)

(2022) Alluminium display 76x92 cm, photographic print on aluminium, 40 000 glass crystals

Sous les pavés, la plage! (1982)

(2024) Alluminium display 76x92 cm, photographic print on aluminium, 35 000 glass crystals

Sous les pavés, la plage! (1984)

(2024) Alluminium display 76x92 cm, photographic print on aluminium, 19 000 glass crystals