The Incredulity of Saint Thomas

The Incredulity of St. Thomas explores the mechanisms of cultural creation and the interplay between art, history, and societal structures, with a particular emphasis on the role of belief in shaping our understanding and experience of art. Drawing on the iconic image of Doubting Thomas and Marcel Duchamp’s Large Glass, Martychowiec constructs a multi-layered narrative that examines the evolution of societal frameworks from modernity to the digital age.

The project begins with Duchamp’s Large Glass, a symbol of artistic revolution and the onset of modernity. Martychowiec then traces the trajectory of capitalist societies, referencing Karl Marx’s Capital and The Fragment on Machines, to illustrate the rise of technology, industrialization, and the commodification of information.

This work is not merely a passive observation but a participatory project, mirroring the communal engagement necessary for establishing a society. The artistic act serves as a catalyst for shared experience and cultural formation, creating a metaphor for the process by which new ideas gain acceptance and eventually become institutionalized.

Martychowiec’s concept of the ‘readyframed’ plays a crucial role in this process. By designating everyday objects as art, he highlights the potential for transforming history into a readymade. The abandoned objects, like broken glass reminiscent of Duchamp’s work, are imbued with historical context and become symbols within the evolving cultural landscape. The artist’s notes reveal that ‘for anything to flourish truly, what is required is the belief which comes from two dimensions and two opposite ‘polars’: the belief (in art) of the artist and the belief (in art) of the spectator.’

The title, The Incredulity of St. Thomas, refers to the biblical figure who doubted the resurrection of Christ until he could physically touch his wounds. This skepticism mirrors the viewer’s initial reaction to the transformed objects, prompting them to question the boundaries of art and the nature of belief.

Martychowiec’s artistic practice often centers on the interplay between the individual and larger systems of power and control. In this project, the individual’s act of recognizing and interpreting the readyframed object becomes a microcosm of the larger societal process of cultural creation and acceptance. By highlighting the inherent subjectivity in assigning meaning to objects and events, Martychowiec challenges the notion of a singular, objective historical narrative.

The Incredulity of St. Thomas is a thought-provoking exploration of the complex relationship between art, history, and society, inviting viewers to question their own assumptions about the nature of reality and the power of cultural symbols. By placing belief at the center of his artistic practice, Martychowiec challenges us to reconsider the role of faith and conviction in shaping our understanding of the world around us.

An excerpt from Notes on the Glass (2016-2018):

I The invisible weight of history

One of the basic ideas of modernity is rejection of the traditional culture which is replaced by the insatiated cultivation of the new. Modern artists like Duchamp would not have been considered from the perspective of the classical tradition. The Large Glass breaks and it is exactly its ‘myth-building function’ (the content, like meaning behind specific elements and their political implications are pushed to a secondary place and become hidden – this is precisely how myths work). At that point, the Glass ceases being a work of art, it acquires historical quality and essentially becomes a relic of art history, in this case, also of modernity. Its content might be valid for further study. However, its mythical quality acquired by breaking shadows everything else. ‘Each time I see a broken glass in the street I think of Marcel Duchamp’ was the beginning of the concept of the readyframed – every object one chooses has already the frame of history upon it, and so every common abandoned object, like a broken glass, may become a work of art; the frame is suggested by the artist, but essentially established by the spectator. The shared consciousness of history and common desire to belong are, generally speaking, the basic prerequisites for establishing culture and common identity.

[…]

II Open source

In his The Fragment on Machines Marx imagines that in an economy where machines do most of the work, the nature of the knowledge locked inside the machines must, he writes, be ‘social’. He then writes of an ideal machine, one which lasts forever and costs nothing. In the sense of contemporary capitalist societies, information is a commodity which does not belong to an individual or organisational body but what Marx calls a ‘general intellect’. If one considers information in the contemporary world a commodity, which in the form of computer data can be replicated without any additional input, Marx’s idea becomes extremely valid.

Information has one different quality from physical commodity – it can spread, circulate and be shared by the society. It can be modified and permanently redeveloped.

In a sense, the common quality of information in this context is similar to that of a cultural symbol. Thus, this work does not belong to anybody but to all (art history).

Meanwhile, the historical development and considerations remain the main focus here as the broken glass installations are placed each time in a different context (both spatially, institutionally and within the artist’s oeuvre), and despite the object being essentially the same, it develops the discourse further with each subsequent installation, i.e. it becomes a metaphor of a historical narrative.

A gesture of declaring such an abandoned object a work of art is nothing else than transforming history into a readymade.

[…]

As much as symbols and relics are rejected in the modern discourse, it is impossible to make them vanish. The broken glass as an object of ambiguous character brings to mind an old story – Saint Thomas is not willing to believe in what is outside of the frame of reason, and so eventually that which is outside of it is brought in so that he can reestablish the frame.

The reference to Thomas brings to mind historical representations on the theme from the Old Masters. Large-scale classical paintings functioned primarily within the context of religious institutions: the large scale was, one could say, reserved for the sacred – the church and the king. Modernity made the common object of glass large (and gave it such soubriquet). In this instance, classical paintings are copied but the case is reversed: the common object of glass remains large and the oil copy of a Caravaggio is made in the postcard format. Miniaturisation imposes simplification and one can say both conditions represent qualities of the contemporary. The illusion disappears and the truth is laid bare.

The process of manufacturing these copies follows the narrative of historical social displacement: the image of the painting is sent from Europe to China, where the painting is copied; it is then sent back and in the process gets damaged, as any postcard does, and as such becomes like Duchamp’s broken glass. This new object, which through scaling follows the opposite narrative to that of the glass – from an object of art history it becomes an object of art – and immediately becomes an object of art history again. The content is replaced with the myth. A small object, however, is different from the large one. It forces intimacy, concentration and yet is a perfect representation of how we experience reality in the present – through miniature reproductions (an example is the screen of our handsets). On one hand, we have the Large Glass and the universal history, on the other a postcard painting and history from the individual existential perspective.

[…]

III From the street to the museum and back to the street

A community which acquires a common identity and thus becomes a culture requires certain validating frames. At this point, a myth must be established and supported by such frames, i.e. through the institutions of establishment. Such institution is, for instance, the museum.

The museum requires relics of the artist’s activity – works of art – which thus function as proofs of the cultural heritage. The historical necessity dictates (and it is in most cases of history true) for the artist’s intention to be then put at the secondary place.

The glass can thus no longer remain a common profane object. Its status has to be elevated, as the society requires a shared factor to represent it and allow its members to identify with. This is understood to occur outside of the frameworks of the economy of understanding (i.e. the case similar to that of a religion). Once validated by the institution, The Incredulity of St Thomas becomes a symbolic object, which under such status is allowed to leave the isolated space of the museum. A circle it has made points to the quality of both information and the readyframed being very much like that of the symbols. And this is exactly how it penetrates the popular culture.

[…]

IV After the creative act

It is clear 21st century curatorial practices have moved very far from their original role and framework. It should not be a surprise, considering the possibility of the role of the spectator is also considerably different to what it was at the beginning of the 20th century. Curators take on active roles in determining the work of art and actively participate in the artistic and historical process.

The incredulity of St Thomas is ‘produced’ a priori and as such it has a ‘growing’ quality. The means for this are curatorial practices or historian practices thanks to the artist making the glass a sort of open-source signifier and value holder.

It does not, however, hold any other prerequisites. The question and artistic intention, here, are precisely the richness of possibilities which the work of art can acquire throughout its ‘historical’ life. […] It is not subjected to the usual process of individual creation or the division of labour. The creative act is taken over by the spectator, curator, critic or historian. The artist follows and constantly re-completes the conceptual value of the work and is an active participant in the ‘after the creative act’ process. The re-completion takes a form of new works of art or installation elements which are always accompanied by a note of artistic self-revaluation.

The incredulity of Saint Thomas

(2016) broken insulated glass panel

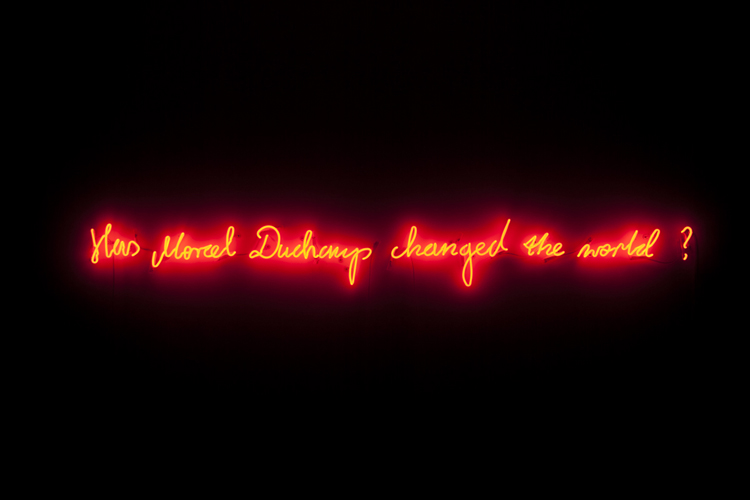

Has Marcel Duchamp changed the world?

(2014) neon 25x220 cm

The bride stripped bare by her bachelors, even

(2016) oil on wood, 15x21 cm

The bride stripped bare by her bachelors, even

(2017) oil on wood, 15x21 cm

The incredulity of Saint Thomas

(2017-2020) broken insulated glass panel

Fountain

(2016) HD Video 00:01:53

After the creative act I - History becomes a readymade, once again. The Northeaster blows.

(2018) installation: pigment print on paper

After the creative act II - History becomes a readymade, once again. The wind from the Sea, the wind towards the Sea.

(2020) chromaluxe prints on alluminium, broken glass panels, aluminium frames 50x65 cm each

The incredulity of Saint Thomas: Limited by history

(2020) oil on wood, 15 x 21 cm, variable number of broken insulated glass panels, dimensions variable

Return of the Real

(2015/2020) 60x45 cm oil on canvas

100 years later in front of the fountain

(2017) neon, 110x140 cm