Tears of Iblis I

Michal Martychowiec

Tears of Iblis

29th June – 27th July 2018

Migrant Bird Space

17-1-102, Lily Building

Vanke City Garden

Houshayu Shunyi District

Beijing

The narrative of the Tears of Iblis cycle presented at Migrant Bird Space in Beijing is constructed through works exploring the ‘image of emptiness’ (made in large formats) and works which on the surface, are more grounded in ‘reality’.

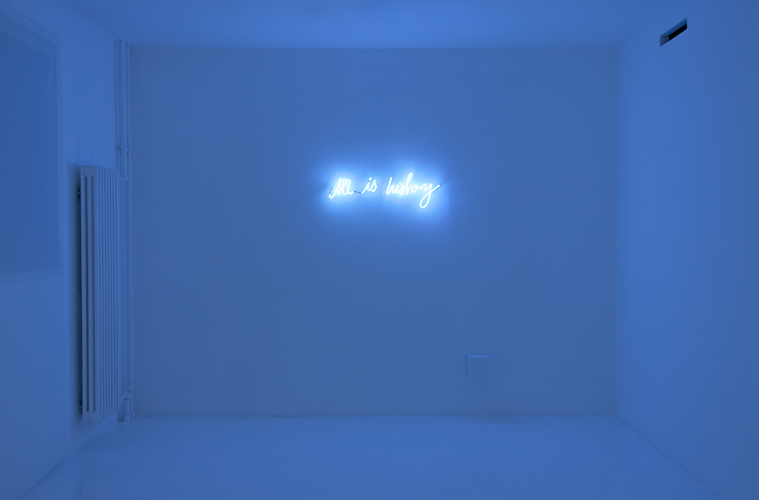

The beginning of the exhibition is marked with an existential neon statement, historically assigned to Buddha. The emptiness in Buddhism cannot be measured through the common Western understanding, because on the contrary, it is not a state deprived of things, but rather a state which contains all things. The visual presentation of this idea can be clearly seen through a photograph created with two historical negatives, the area where one image covers the other does not create the overlaying of two, but rather cancellation of two, and so the white photographic paper shines in the same way as the words of the neon. The large rock placed in the centre, one could say a reminder of the arte povera movement, is however, not only a memory of existing art history but also a memory (element) of an installation created in 2012 which originally re-enacted an image of an ancient parable.

Further works explore either the empty natural landscape or emptiness of the historical landscape. In both cases, they become entry points for development of historical and symbolic considerations (on either personal or universal level).

In this sense, a work from 2012, neon All is history, which closes the exhibition, points to the important concept of the readyframed. The concept of the readyframed was created in 2016 together with The incredulity of St Thomas project. Analogically to the readymade, which is constructed on the base of artistic activity being that of a manual creation (painting, sculpting), readyframed is using photography or film as its base. Any object one chooses has an existing frame (context) of history around it, and as such is already a conceptual work of art (committed thanks to, but not by, the historians). The artist doesn’t essentially point to the object, but to the frame. Once established, the frame functions in a similar manner to contemporary blockchain technology, it is shared and cannot vanish as long as it remains within the consciousness of the social body. The concerns of Marx and Engels on the matters of production and division of labour within artistic practices, so valid to Duchamp, become void.

And so these works, at first meant to be evaluated from the perspective of ‘experience’ are actually frames for historical considerations, for they hold: references to history, are framed by history and are to become part of history. In a sense, history is what eventually saves us, from the emptiness we face in these works. This is also true of the portrait from La Chambre de Labastrie series, from which we are looked at just before leaving the final exhibition space. The woman portrayed in this work has essentially lost her identity and became ‘framed’ by a historical story, and thus became a hero of the new mythology created by the artist. Although, as a person, destined to be lost and forgotten, through the ‘work of [artistic] creation’ she became part of the ‘work of salvation’, in other words, of history.

Michal Martychowiec, 2018