Tears of Iblis II

Michal Martychowiec

Tears of Iblis

25th August – 14th September 2018

Signum Foundation Gallery

ul. Piotrkowska 85

Lodz

After all, there is nothing in creation that is not ultimately destined to be lost: not only the part of each and every moment that must be lost and forgotten – the daily squandering of tiny gestures, of minute sensations, of that which passes through the mind in a flash, of trite and wasted words, all of which exceed by great measure the mercy of memory and the archive of redemption – but also the works of art and ingenuity, the fruits of a long and patient labour that, sooner or later, are condemned to disappear. It is over this immemorial mass, over the unformed and immense chaos of what must be lost that, according to the Islamic tradition, Iblis, the angel that has eyes only for the work of creation, cries incessantly. He cries because he does not know that what one loses actually belongs to God, that when all the work of creation has been forgotten, when all signs and words have become illegible, only the work of salvation will remain indelible.

Giorgio Agamben

Tears of Iblis is one of the exhibition cycles created by Michal Martychowiec. In this particular case, it is moreover third, out of four, within the narrative of another series of exhibitions – Reading history – taking place at Signum Foundation Gallery throughout 2018.

This newly contextualised body of work explores cultural development in the modern and post-modern West. The perspective of breaking from the historical narrative and tradition of the symbolic language and its consequent cultural emptiness of contemporary societies become uncovered through the means by which the spectator approaches and explores presented ‘images of destruction’.

The modernist language abandoned the iconographic tradition with Malevich and the Black Square. This new vision of art was no longer grounded in history and classical considerations, but in the newly changing world and its materialist character (paradoxically, this ‘newly’ changed world begun half a century earlier with the industrial revolution); and so for instance utilising every day, common, mass-produced objects, like in the case of the readymade. The importance of the materialist context in the case of this new destructive paradigm becomes clearer by following the distinction of two forms of violence made by Walter Benjamin. Mythical violence destroys and gives birth to the new. Divine violence produces destruction which leaves nothing behind. If god created the world from nothingness he can turn it back into nothingness. However, in the framework of that new materialist philosophy, since god is dead, the divine destruction can no longer be possible and becomes material destruction which, on the contrary, leaves traces, like ruins, etc. It is in this sense, we ought to look at the Black Square, Malevich’s ‘destruction of the icon’ (and so the destruction of god, holy, history, etc.) and then consider his famous statement: ‘The image that survives the work of destruction is the image of destruction’.

However, the clear historical struggle which has followed shows that once the paradigm is replaced with the image of its demise, what is left to us? Malevich’s gesture of destruction had a value because at the time it created a transition into a new (materialist) ‘metaphysics’. But breaking from tradition, as history teaches, simply creates a new tradition, in the same way, that abandoning aesthetic (like in the case of minimalism) simply creates a new aesthetics. And so in the contemporary context the meaning of the Black Square on the ground on which it was meant to function, has been lost, because at this point, it can only be understood in the context of history (from which Malevich tried to break off or which it rather tried to destroy). Later modern and postmodern art which has followed this new narrative consequently became repetition of a repertoire of the very same ideas, which being deprived of the actual socio-political context became, no wonder, empty.

Iblis ‘cries because he does not know that what one loses actually belongs to God’, however as much as divine destruction is no longer possible within the materialist framework, whatever is lost, in the same sense, has nowhere to return to and so still remains under the cover of such emptiness.

Tears of Iblis is constructed with works which in several instances represent the images of emptiness of the modernist tradition and the new (still empty and hidden) symbols, history and myths awaiting their foundation. These works do not (once again) destroy the current ‘icon’ as Malevich did, but rather look for new icons (the holy) in the images of what has been lost and destroyed. They are thus installed together with the third chosen instance of a historical game which is being reenacted throughout the course of the exhibition series at Signum Foundation. In fact, what we witness is situation of the 1846 game just before the most iconic move in the history of Japanese Go would have been made.

Several works make references to historical narratives and most importantly and unavoidably to the Black Square. The most obvious one is a framed stone ‘Death of Plutarch’ placed symbolically in the upper corner of the space. It represents, in fact, the very mentioned historic move which we are not meant to witness at the board. Furthermore, this symbolic object takes what would have been the holiest space, which Malevich once used for his Black Square, and this installation gesture precisely is meant to bring back the holy into being. Of course, one could say Plutarch represents history, and his death, himself becoming history. However, the primary value of this work under the group title Naming history does not lay in its recalling or representing historical events, whose meaning one would normally attempt to interpret in the context of the exhibition or the project. The stone, through an artistic decision, becomes assigned and placed within a context of the historical game. It becomes a result of the artistic strategy of looking, creating and assigning the meaning, which is available to the artist through placing an object in the context of life and history. It consequently, establishes the value of the work of art and the artistic activity as one, which allows creation of relics of either fictional or true historical narratives. These relics embody the format of symbols, i.e. their internal construct and how they are meant to function within larger narratives, such as this one.

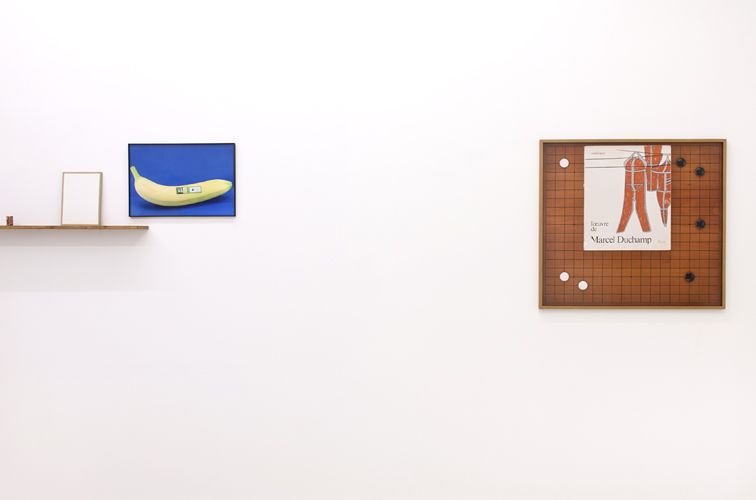

The elements composed within Notes from the board both refer to specific narratives within Martychowiec’s practice (in some cases clear thanks to the references available in preceding exhibitions, and in some requiring further references which are to be provided in Journey to the West), but furthermore they refer to additional two parallel narratives: a socio-political one (black

square turned red square turned a product of daily [=non-historical] consumption) and one to do with the means of dealing with the historical tradition (represented by a damaged catalogue raisonné of Marcel Duchamp).

The problem of dealing with tradition is also clear with the work Vanito Vanitas, where the content of the image of emptiness (Vanitas) becomes subjected to the process it meant to signify. This image embodies the concept of Tears of Iblis most clearly, as it remains a representation of cultural emptiness in both cognitive and visual way, and additionally through its very process representing the failure of the work of destruction.

Most importantly, however, two symbols taken from the historical void (the contemporary) are presented. The panda and rabbit Josephine have become two predominant symbols in Martychowiec’s practice. In Tears of Iblis they are merely mentioned and thus function as curious everyday phenomena. For example, the panda marked organic banana (a symbol of history introduced in the first exhibition) or a stuffed panda filmed in the museum with Marcel Duchamp chatting in the background. Same could be said about the rabbit Josephine making an imperialistic (and empirical) claim with her cage and thus drawing metaphor of the contemporary human condition (of course, with another reference to a specific point of socio-political history represented by Warhol’s Empire).

Of course, like the fading slide ‘once is gone’, all these narratives are also destined to be lost, but this is also precisely their point. The work of creation is meant to be forgotten, so that the introduced symbols, free from original constraints can acquire broader cultural significance.

In Tears of Iblis the modernist language becomes aesthecised in order to prepare the ground for a solid paradigm, not based on ever-changing achievements of science, technology, etc. The means of destroying the ‘image of destruction’ lay precisely in the reestablishment of the myth, so that the ‘divine violence’ (destruction) can again be effective. After all, what, eventually and always remains indelible of the work of (artistic) creation, are – the concepts (poetry) and symbols. In other words, the work of salvation, the mythology.

Michal Martychowiec, 2018