Tears of Iblis III – All that is solid melts into air

Michal Martychowiec

All that is solid melts into air

21st January – 12th March 2021

Rodríguez Gallery

ul.Wodna 13/4

61-782 Poznan

‘After all, there is nothing in creation that is not ultimately destined to be lost: not only the part of each and every moment that must be lost and forgotten – the daily squandering of tiny gestures, of minute sensations, of that which passes through the mind in a flash, of trite and wasted words, all of which exceed by great measure the mercy of memory and the archive of redemption – but also the works of art and ingenuity, the fruits of a long and patient labour that, sooner or later, are condemned to disappear. It is over this immemorial mass, over the unformed and immense chaos of what must be lost that, according to the Islamic tradition, Iblis, the angel that has eyes only for the work of creation, cries incessantly.’

Agamben, Creation and salvation. In: Agamben, G. (2010) Nudities. Stanford University Press.

Tears of Iblis is one of three exhibition cycles curated by Michal Martychowiec with his own works. Each of the three cycles makes a symbolic reference to specific points in history and so: What remains the poets provide represents Romanticism and reestablishes certain aspects abandoned in the modern discourse. Tears of Iblis deals directly with the following modernity and destruction of the Icon, and explores cultural development in the modernist West and similarly in the post-Cultural Revolution China. Through Journey to the West the artist presents a complex system within his practice. Various symbolic elements, like the panda, rabbit Josephine, broken glass or glass crystals constitute a cosmos of signifiers which course runs parallel to our own contemporary world. And it is thus that all works of Martychowiec have a deeply engraved political message.

One of the recurring elements in the artist’s practice and this exhibition is glass crystal. Martychowiec introduced crystals with his installation from 2014 – Sous les pavés, la plage! The title of the work holds a clear reference to the France’s 1968 student protests (of which it was one of the slogans). ‘Under the cobblestones, the beach’. If the cobblestones were to represent the city and the contemporary civilisation, the sand was to symbolise nature and freedom. As the artist originally wrote: ‘The installation is constructed through an intricate study of historical frameworks: the poetic title somehow provides us with, as in most cases, romanticised image of history, but so is the visual language: the blue walls, the beach chair and umbrella, they all bring an image of some sort of vintage holiday advertising. Only the crystals which replaced the sand bring us closer to the contemporary, for in the language of contemporary media nothing is allowed to be real, i.e., imperfect, and can there be a more perfect replacement for sand, if not the crystal which, incidentally, is made of it.’ 1968 was a breakthrough moment in history, as the civil rights movements failed to prevent the later development of the neo-liberal policies throughout the world resulting in concentration of wealth, decline of the working and middle classes and then perhaps even rise of the right-wing sentiment among the populations of the present.

Thus, the crystal for Martychowiec became representation of exactly that new age. In that new landscape freedom remains but an attractive illusion of what it actually is. In a world where to be is no longer to exercise freedom through acts and thought, but to consume, continuously in the ‘new spirit of the age: gain […] forgetting all but self’ as was famously written in a working-class journals early on during the industrial revolution in United States.

Taken this context into consideration let us look at the works: at the entrance we are ‘greeted’ with a hand offering a handful of crystals. What remains the poets provide reenacts a historic work by Giovanni Anselmo – Hand indicating. It marks another point in Martychowiec’s historical narrative and, specifically, positions his practice in the context to the passed post-modernity.

Anselmo’s strong gesture, as its title suggests, offers essentially an empty hand and thus not what normally the hand would hold, but rather the direction. Hence, what is developed within the discourse is the framework rather than the value of individual elements – a typical post-modern approach. What Martychowiec is, however, indicating, is a certain value contained by the means of symbolic representations developed within his continuous artistic practice. The direction is suggested, but its value and meaning can only be determined in regards to the specific signifier. The crystals are offered in a tempting fashion. Will one see through and understand the price one would have to pay for accepting?

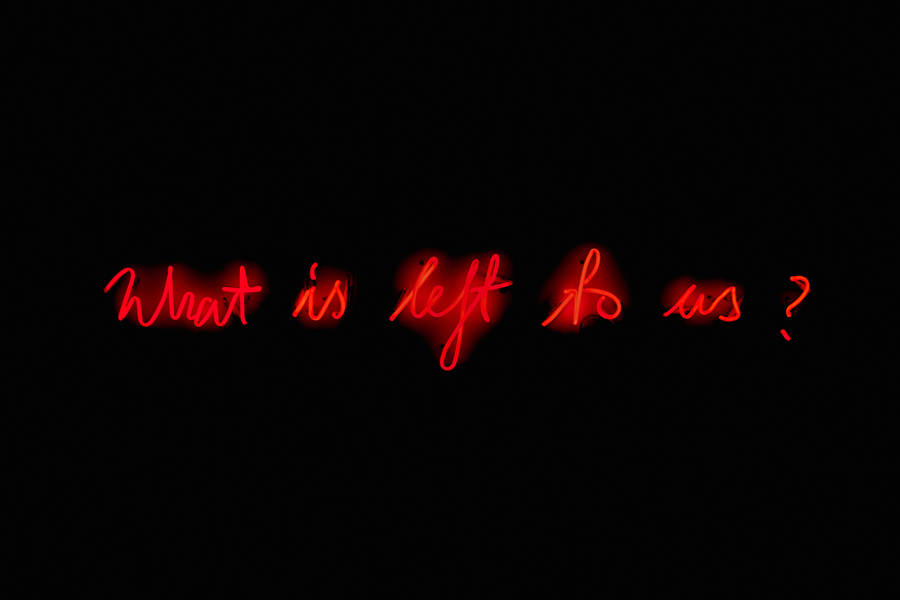

Accompanying this work, to the left, we see the recent neon from the daily questions series: What is left to us? This work, as most of Martychowiec neons functions as a sort of titular entity and could be said to title this part of the exhibition and installation as a whole and individually as it would be expected to be asked by the visitor with every work, he/she might stumble upon. What is thus left to us? Accepting this artificial perfect and cold beauty of the sparkle while becoming apathetic and passive? Or?

In the centre of the space stands a pavement plate with a large crystal embroidered onto the upper edge, reminding of a compass in another work by Anselmo. Arte povera is a series of sculptures made using pavement plates (as a more contemporary replacement for cobble stones) and crystals.

On one hand, it would seem the title could be taken quite literally as the ‘poorness’ of this work also reflects the generic value of materials it has been made with indeed (glass and concrete). Arte povera’s origin takes place interestingly around the same time as the civil rights movement and could be said some of their political implications are in line. The original arte povera’s political dimension had to do with general modes of art’s valuation at the time. Here, the sparkles of the large crystal attract the spectator, although one might ask, why would such ‘poor’ and common materials attract? Can the crystal with its sparkle be alike Anselmo’s compass and offer any direction? On the other hand, these works offer a certain personal mirroring and questioning of our contemporary condition, in a way typical to Martychowiec. For the spectator might fail to find answer as to why the work attracts. Is it art that is ‘poor’? Or is it that our life has become so? And, once again, if so, what then is left to us?

On the opposing wall to the neon, we face an image whose part is covered with a layer of crystals Sous les pavés, la plage! (1989). The date included in the title is one suggestion but for those familiar with the events in Beijing at that time the image is known. It is the nicknamed ‘tank man’ – an unidentified Chinese man who stood in front of a column of tanks leaving Tiananmen Square on June 5, 1989, the day after the Chinese military had suppressed the Tiananmen Square protests. The artist is utilising historical images as representations of an ongoing struggle between freedom of the individual will and the power system. In such way the events from 1968’s France become symbolic representation of something universal and repeated in history.

Another similar display deeper in the gallery is wide open, 40 000 crystals scattered underneath it on the floor. The image depicts a Vietnam War protester placing a carnation into the barrel of an M14 rifle held by a soldier of the 503rd Military Police Battalion in Washington in 1967, and image from which the famous expression ‘flower power’ derives.

Both of these works, coming from the same series, have a possibility of a twofold presentation. A display closed, with the layer of crystals censoring the part of historical subversive action, uncomfortable to those in power and deemed preferably forgotten. The power of an execution platoon or a line of tanks is something which might seem impossible to face as an individual, after all.

Wouldn’t it be then better to simply succumb and accept and consume the cold and ‘dead’ beauty of ‘crystal’? After all, if consumption needs are met, is there any need for anything else. For those holding the key to these displays there is another possibility. Open them, let the crystals pour out underneath and a somewhat different possibility presents itself.

From the front of the gallery, one goes through the narrow passage illuminated with the blue light from the neon All is history, the statement which in the context of the artist’s work should be understood as an active and positive call.

In the back room a ‘construction’ or a ruin-like area with sand and pavement blocks is presented with a projection behind.

The fire and the rose are one is the second out of a film trilogy by Martychowiec. The series investigates and constructs an ongoing reinterpretation of history using symbolic locations, frameworks of historiography, historical, political, and sociological ideologies, and various cultural relics. The film is constructed, similarly to The shrine to summon the souls, with two parallel narratives. One is the text of T. S. Elliot’s Four Quartets which suggests on many levels means of reading of the visual part which presents three historically symbolic sites: former site of Pruit-Igoe social housing project in St. Louis, Ordos City in Inner Mongolia and ruins of the Greek village of Levissi located now at the Turkish coast. The three locations present historically symbolic ruins and each facilitates a new perspective in consideration to our present circumstances.

The film begins in St Louis, which like many major American cities in the early 50s was facing an increasing number of migrants from the rural areas. To solve the housing problem the city council decided to construct a housing project following Le Corbusier’s Athens Charter. A complex of 11-storey high towers was completed in 1956. The project offered family flats with facilities many of its inhabitants-to-be never had had access to: modern bathrooms and kitchens, laundry rooms and other communal areas. Despite that the project started declining only a few years later. The 60s produced a new landscape, the American Dream was not in accord with the idea of community, it propagated an isolated individual whose life concentrated around consumption (something young hippies later on would be vividly protesting against). Inhabitants of the cities would move to the suburbs and a housing solution was no longer necessary. By mid 60s the complex declined. It was occupied only in a third and it became dangerous and crime-infested; it was said police would not even dare to arrive for interventions. Between 1972 and 1976 the whole complex (apart from the school and chapel) were demolished. What followed was a neoliberal period of manufacturing outsourcing which further contributed to the region’s and city’s decline. St Louis was not to recover. Up to this day, in the centre of the city, a quarter of abandoned rubble of Pruitt-Igoe is buried underneath a wild park.It is at this site that the story begins. The spectator is invited to follow the narrator into a ‘garden’, where many narratives of the past and present meet.

From Missouri we move to Inner-Mongolia and the City of Ordos, which several years ago was listed among the so called ‘Ghost Cities’ by the Western Media. These abandoned and ruined cities presented in pictures, were in most cases simply projects-in-progress, and so essentially a construction site, as the central government invested in building a 2 mln inhabitants conglomerates over only a couple of years, a scale not really familiar to the Western audiences. The common commentary followed a typical neoliberal idea, similarly assigned to Pruit-Igoe – a crazy utopian vision, which could not possibly have succeeded. By 2017 the city was already inhabited in 30%. Nevertheless, Ordos still remains relatively empty in many parts. On its account several rushed building projects were undertaken and many had to be abandoned.

In the middle, the film moves on to the Turkish coast and an abandoned Greek village. But from that point on the film will move back and forth from Ordos to Levissi, then briefly back to Ordos to then conclude back at the seaside.

Ordos city became a middle point of the film, because it is a ‘ruin’ of a different sort than the two others. It is also a place where one could say issues of urban planning (represented by Pruitt-Igoe) and social and racial planning (like in the case of Levissi) meet. It is also the place in-between past and future, as the narration of the text moves through time and memory. The feeling of desolation also brings a different sense of uneasiness. An issue of cultural minorities in China and the policies of the Central Government. ‘The people of the plains bring culture and wealth to those poor inhabitants of the steppes.’ The locals might be willing to accept the tempting offer, the cost of which we might yet to learn.

The film concludes at a different kind of ‘ghost town’ – ruins of Levissi located in the historic region of Lycia, now in Turkey. Prior to 1922, the town was solely inhabited by the Greek Christian population. In 1914 the Ottoman authorities began persecution of the local Greeks as a result of larger plans of ethnic cleansing. For the following 8 years the Greeks were tortured and murdered. What is now recognised as genocide of Ottoman Greeks ended in 1922 with deportations of the small number of remaining Greek population.

The three sites with their historical, political and social backgrounds elicit contemplation on time, history and meaning of our life in the present. The final scene from The fire and the rose are one leads on to the 3rd film of this cycle. Each of the mentioned locations brought forth contemplation on time and history, thoughts on the past, present and future. The view of the Aegean sea brings forth another story to mind, after all the ancestors of Greeks in the region, the Lycians, were to fight in the defence of Troy and the sea before our eyes as the film concludes is the one on which the Achaean ships once supposedly appeared. And so a new chapter follows. In the camp of Achilles.

Michal Martychowiec, 2020