Reading history

Michal Martychowiec

Reading history

12th May – 30th May 2018

Signum Foundation Gallery

ul. Piotrkowska 85

Lodz

Reading history is the 1st out of the cycle of 4 exhibitions of Michal Martychowiec held at Signum Foundation throughout the year.

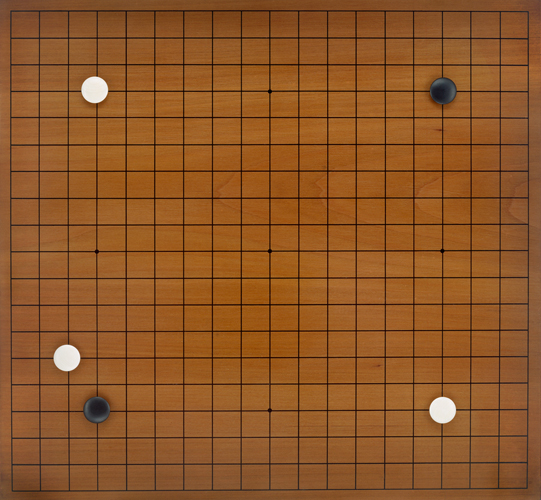

The project is a metaphorical investigation of the structures of history, artistic practices and in a sense, life of each individual. The idea is based on the construction of the ancient Chinese board game weiqi, in English known as Go.

As Martychowiec writes ‘the stone itself is a nothing, but when placed on the board it becomes representation of an idea. It is, indeed, so much alike any gesture of an artist, where the medium is a mere representation of the concept, and which once committed, remains and influences not only what precedes it, but most importantly what follows.’

Upon creation of an idea (either within a game or an artistic practice) its meaning or significance might not be clear, neither for the spectator, nor its creator, and one might have to wait for what is to follow in order for the true meaning of the gesture to surface. Of course, there are these ‘moves’ in the game, or these artistic gestures or events in history, which are groundbreaking. They change the meaning and significance of history and time (they give meaning to the past and they create the future), or they change the meaning of anything the artist has committed up to that time.

The historical value of Go is unprecedented, for as much as many of historical documents in China have not been preserved, records of Go games played have been kept, and the oldest available to us date to as early as AD 196. The project thus, as its title would suggest, is structured not through creation of game arrangements, but through re-enactment of historical games. It is thus divided into different serial elements, among other objects, they create sub-series of:

actual full re-enactments of historical games (eg. Reading history 2016-1846), which are developed on a wooden board throughout the duration of exhibitions and influence the context, meaning and framework of all the works of art around them

large format photographs re-enacting and depicting chosen moments from games in Go history (e.g. Reading history #1 (2018-196))

large format photographs documenting notes, images and objects placed within the frame of historical games, under the title ‘Notes from the board’ (e.g. Notes from the board #1)

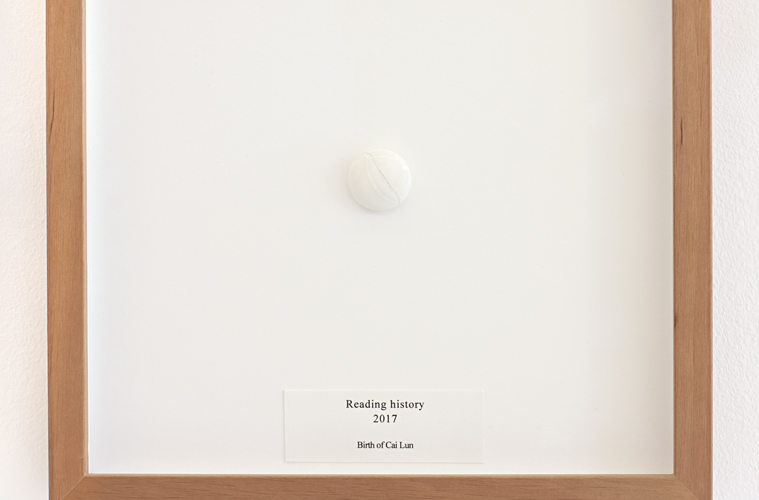

and lastly, historical stones, functioning like framed relics under the title Naming history. Here the approach is slightly different and connected to the initially quoted statement of Martychowiec. Before the used stones are chosen, following the original context, they hold both all the ideas they were used to represent, and ideas they can still represent. The latter applies up to the point, they are chosen by the artist, aesthetised (they become works of art and can no longer be used to represent new ideas) and given meaning, based purely on the artistic decision rather than scholastic study: by placing them in the context of history, and by placing them in a context of another historical game.

The structure of Go, as mentioned, being so alike to that of history, provides an interesting parallel. For those knowing nothing of the game’s structure, the large-format photographs of the chosen moments of historical games, mean no more than geometrical compositions. This aesthetic layer is important because it has always been inseparable from art (for history has taught us rejection of any aesthetics, like in the case of minimalism, leads only to creation of new aesthetics). But those who know of the game, or even more so, the ones who are masters of it, are capable of reading far more from that one simple geometrical composition: they might be able to estimate its placement on the timeline of history, and tell about emotions or approach of those who played it, perhaps even guess the players’ age, they might be able to, with some degree of error, reconstruct the order in which the stones were placed, and then, of course, they might be able to make realistic guesses of what followed and what was the game’s result. This can be said equally about historians and about those who are learnt to read cultural tropes, symbols and relics.

In the context of the cycle of exhibitions at Signum Foundation Gallery, Reading history provides somewhat structural frames to the whole cycle, as much as the project does to the whole of Martychowiec’s practice. Despite that, only the first exhibition is named after the project and consists solely of works from within it.

The only element which remains throughout the whole cycle of 4 exhibitions or rather is developed throughout all of them and completed within the last one, is a wooden board re-enacting a game played in 1846 in Japan between an established master Gennan Inseki and then 17 years old Kuwahara Shusaku. This game has become historic not only as it contains one of the most famous ‘moves’ in the history of Japanese Go, but also because it shows a struggle of the young to overcome the old, and so the beginning of a new chapter in history. It shows the brilliance of youth, a kind of moment of genious which in one’s life occurs only once, and a gesture which can turn, what was believed to had been bad moves, into good moves, in other words give meaning to the gestures which up to that point had only held contingency of their true ideas.

The first exhibition is constructed on the base of this structural historical frame so that the meaning of its elements cannot be understood by most from this one modest presentation and it is necessary to witness the whole cycle to grasp the full meaning of it. It is, of course, the same with it not being possible to evaluate the value of a complex artistic practice purely based on one singular work or exhibition. The space in each of the exhibitions is divided into modular parts and Reading history will be followed with:

What remains the poets provide

The Tears of Iblis

Journey to the West

The arrangement of the works within the cycle is not organised chronologically but rather based on their relation to one another. On top of the two narratives: that of the game from 1846 and that of Martychowiec’s practice as a historical construction, various moments of art history and history reappear here and there throughout the exhibitions.

Michal Martychowiec, 2018